Experience the world with us

Friday, June 28, 2013

Thursday, June 20, 2013

How Hieroglyphics were Originally Translated

Hieroglyphics were elaborate,

elegant symbols used prolifically in Ancient Egypt. The symbols decorated

temples and tombs of pharaohs. However, being quite ornate, other scripts were

usually used in day-to-day life, such as demotic, a precursor to Coptic, which

was used in Egypt until the 1000s. These other scripts were sort of like

different hieroglyphic fonts—your classic Times New Roman to Jokerman or

Vivaldi.

Unfortunately, hieroglyphics

started to disappear. Christianity was becoming more and more popular, and

around 400 A.D. hieroglyphics were outlawed in order to break from the

tradition of Egypt’s “pagan” past. The last dated hieroglyph was carved in a

temple on the island of Philae in 395 A.D. Coptic was then written and spoken—a

combination of twenty-four Greek characters and six demotic characters—before

the spread of Arabic meant that Egypt was cut off from the last connection to

its linguistic past.

What remained were temples and

monuments covered in hieroglyphic writing and no knowledge about how to begin

translating them. Scientists and historians who analyzed the symbols in the

next few centuries believed that it was a form of ancient picture writing.

Thus, instead of translating the symbols phonetically—that is, representing

sounds—they translated them literally based on the image they saw.

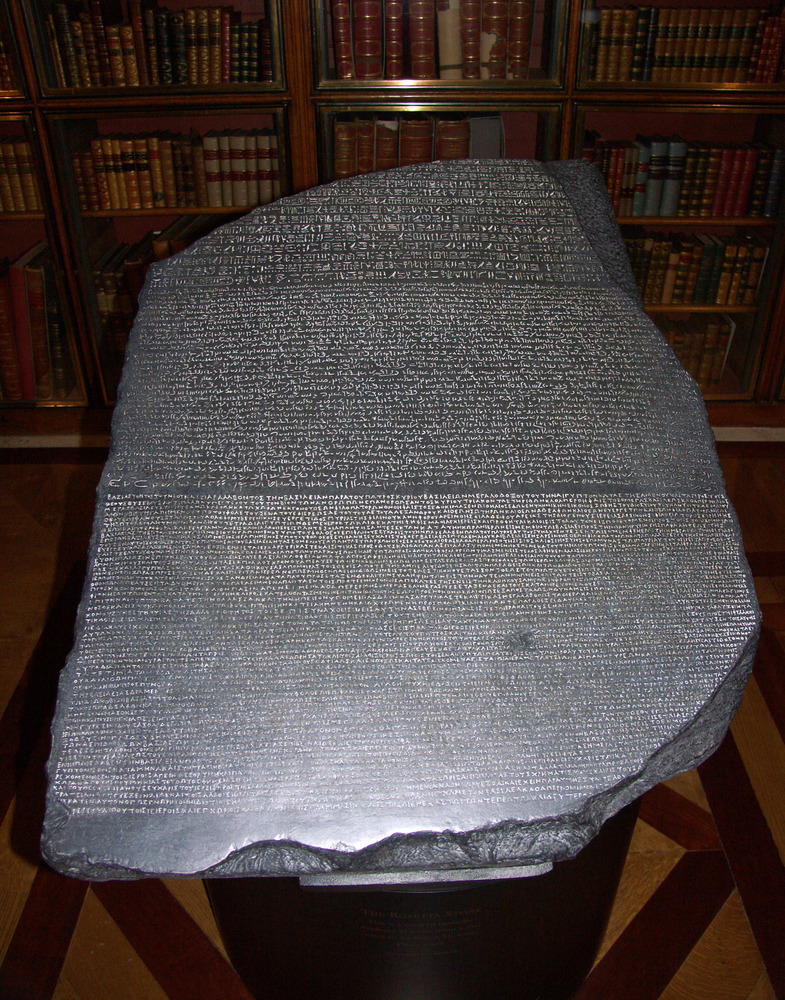

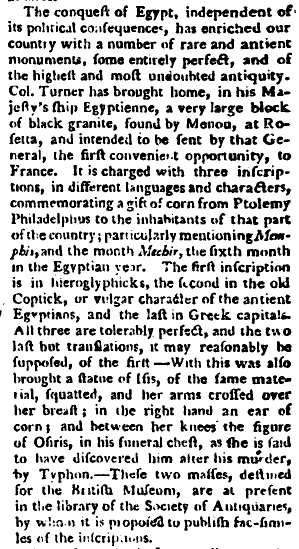

It wasn’t until July 19, 1799

when a breakthrough in translation was discovered by French soldiers building

an extension on a fort in el-Rashid, or Rosetta, under the orders of Napoleon

Bonaparte. While demolishing an ancient wall, they discovered a large slab of

granodiorite bearing an inscription in three different scripts. Before the

French had much of a chance to examine it, however, the stone was handed over

to the British in 1802 following the Treaty of Capitulation.

On this stone, known as the

Rosetta Stone, the three scripts present were hieroglyphics, demotic, and

Greek. Soon after arriving at the British Museum, the Greek translation

revealed that the inscription is a decree by Ptolemy V, issued in 196 B.C. in

Memphis. One of the most important lines of the decree is this stipulation laid

down by Ptolemy V: “and the decree should be written on a stela of hard stone,

in sacred writing, document writing, and Greek writing.” The “sacred writing”

was hieroglyphics and “document writing” referred to demotic—this confirmed

that the inscription was the same message three times over, providing a way to

begin translating hieroglyphics at last!

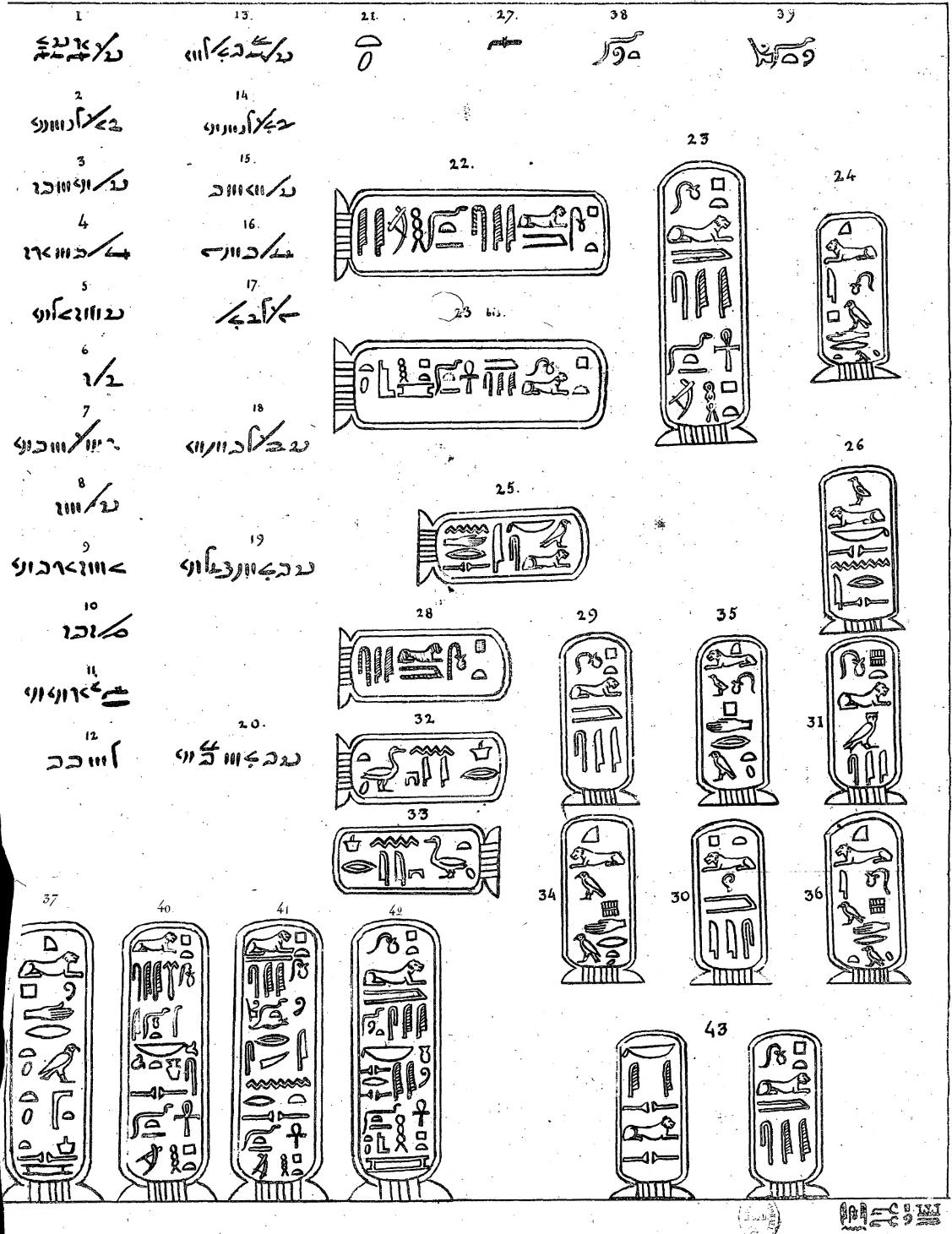

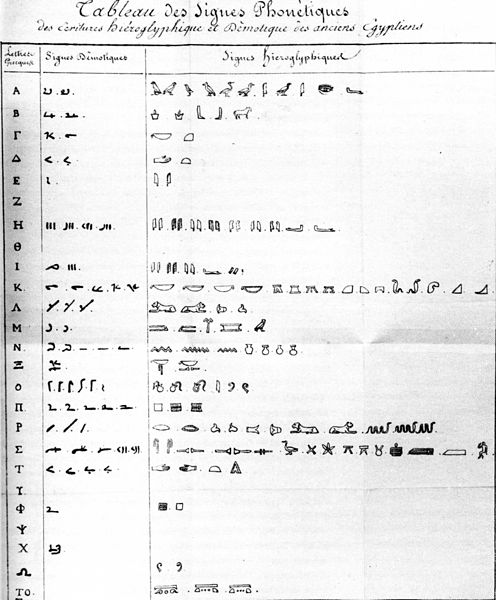

One of the big problems

encountered was that they could try to translate written text all they wanted,

but it wouldn’t give the translators an idea of the sounds made when the text

was spoken. In 1814, Thomas Young discovered a series of hieroglyphs surrounded

by a loop, called a cartouche. The cartouche signified something important,

which Young hypothesized could be the name of something significant—kind of

like capitalizing a proper noun. If it was a pharoah’s name, then the sound

would be relatively similar to the way the names are commonly pronounced in

numerous other languages where we know the pronunciation.

However, Young was still

working under the delusion that hieroglyphs were picture writing, which

ultimately caused him to abandon his work which he called “the amusement of a

few leisure hours”, even though he had managed to successfully correlate many

hieroglyphs with their phonetic values.

A few years later,

Jean-Francois Champollion finally cracked the code in 1822. Champollion had a

long-time obsession with hieroglyphics and Egyptian culture. He’d even become

fluent in Coptic, though it had long since become a dead language. Using

Young’s theory and focusing on cartouches, he found one containing four

hieroglyphs, the last two of which were known to represent an “s” sound. The

first one was a circle with a large black dot in the centre, which he thought

might represent the sun. He dug into his knowledge of the Coptic language,

which he hadn’t previously considered to be part of the equation, and knew that

“ra” meant “sun.” Therefore, the word that fit was the pharaoh Ramses and

the connection between Coptic and hieroglyphics was now perfectly clear.

Champollion’s research provided

the momentum to get the ball rolling on hieroglyphic translation. He now

demonstrated conclusively that hieroglyphics weren’t just picture writing, but

a phonetic language. Champollion went on to translate hieroglyphic text in the

temples in Egypt, making notes about his translations along the way. He

discovered the phonetic value of most hieroglyphs. It was a good thing he kept

extensive notes, too as he suffered a stroke three years later and died at the

age of 41. Without those notes, much of the progress made on the translations

would have been lost.

Taken from: http://www.todayifoundout.com/index.php/2013/06/how-hieroglyphics-were-originally-translated/ [20.06.2013]

Click here if you want to go to Egypt

Thursday, June 13, 2013

Maasai Mara, Home of the Great Wildebeest Migration in Kenya

The annual Wildebeest Migration at the Maasai Mara is a natural cycle that

replenishes and renews the grasslands of East Africa. Each June, around

1.3 million Wildebeest gather in the Serengeti to calve.

They slowly

mass into a huge single herd, until the dry season withers their supply

of fresh grass.

The scent of rain to the North begins to draw the herd throughout July,

and soon the planet’s greatest animal migration is underway.

This is one of the remarkable wildlife attractions that make's Kenya one

of the best wildlife destinations in the world. Kenya’s most popular

attraction, the Mara was awarded its title for its sheer volume and

variety of game.

One traveller summed up the appeal of the Maasai Mara Reserve;

“This is the total sensory experience holiday. Your senses are

constantly stimulated by the sights, smells and sounds of the Mara and

its many inhabitants. The thrill of leaving camp at dawn, in search of

big cats is an experience that is difficult to repeat.”

There is no better time to visit the Mara than during the Great Migration. The sound of the approaching herd is a deep, primal rumbling of thundering hooves and low grunts.

There is no better time to visit the Mara than during the Great Migration. The sound of the approaching herd is a deep, primal rumbling of thundering hooves and low grunts.

The sight of the wildebeest is staggering- a continuous charging mass

that stretches from one horizon to the other this endless grey river of

life is mottled with black and white as zebras join the throng.

Over the course of the migration, visitors to Kenya will have the

opportunity to follow the progress of the herds and experience the full

grassland cycle firsthand.

In the Maasai Mara, Africa’s largest concentrations of predators are

drawn to this perfect opportunity for easy hunting. Lions are frequently

seen attacking the herds - especially at night- dragging down

straggling individuals.

At the same time, packs of Hyena freely weave throughout the herds, singling out and separating the young and the weak.

Predators are not the only obstacles that the wildebeest face. Kenya’s

heavy rainfall in the highland Mau escarpment has turns the Mara River

into a raging torrent.

As happens each year, the herds will gather at the banks in preparation for the most perilous stretch of their journey.

As sheer pressure builds, the herds are finally forced to surge into the river, often hurling themselves off high banks.

In the struggle across the Mara River, many are drowned or swept away by

strong currents. The crossing attracts massive crocodiles who each year

awaits this season of bounty.

By September the herds will begin reaching their goal, and spreading out to graze across the expanse of the Mara.

For this beautiful game reserve, it is a time of renewal, as the dung

from the visiting herds fertilizes the plains. October will see the

herds turn southward and repeat the same journey back to the Serengeti,

where the renewed grasslands await.

The Migration is the planet’s last great epic of life and death. Of all

the calves born in the Serengeti, two out of three will never return

from their first and most demanding migration.

It is this inextricable binding of renewal and sustenance, feast and

famine, life and death that makes this event one of nature’s greatest

wonders.

The migration can be experienced on early morning game drives in customized vehicles, walking safaris with Maasai Warrior guides, horseback safaris in areas surrounding the Mara, or even from hot air Balloon safaris over the herds.

Taken from: http://www.magicalkenya.com/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=194&Itemid=194 [13.06.13]

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)