on

June 18, 2013

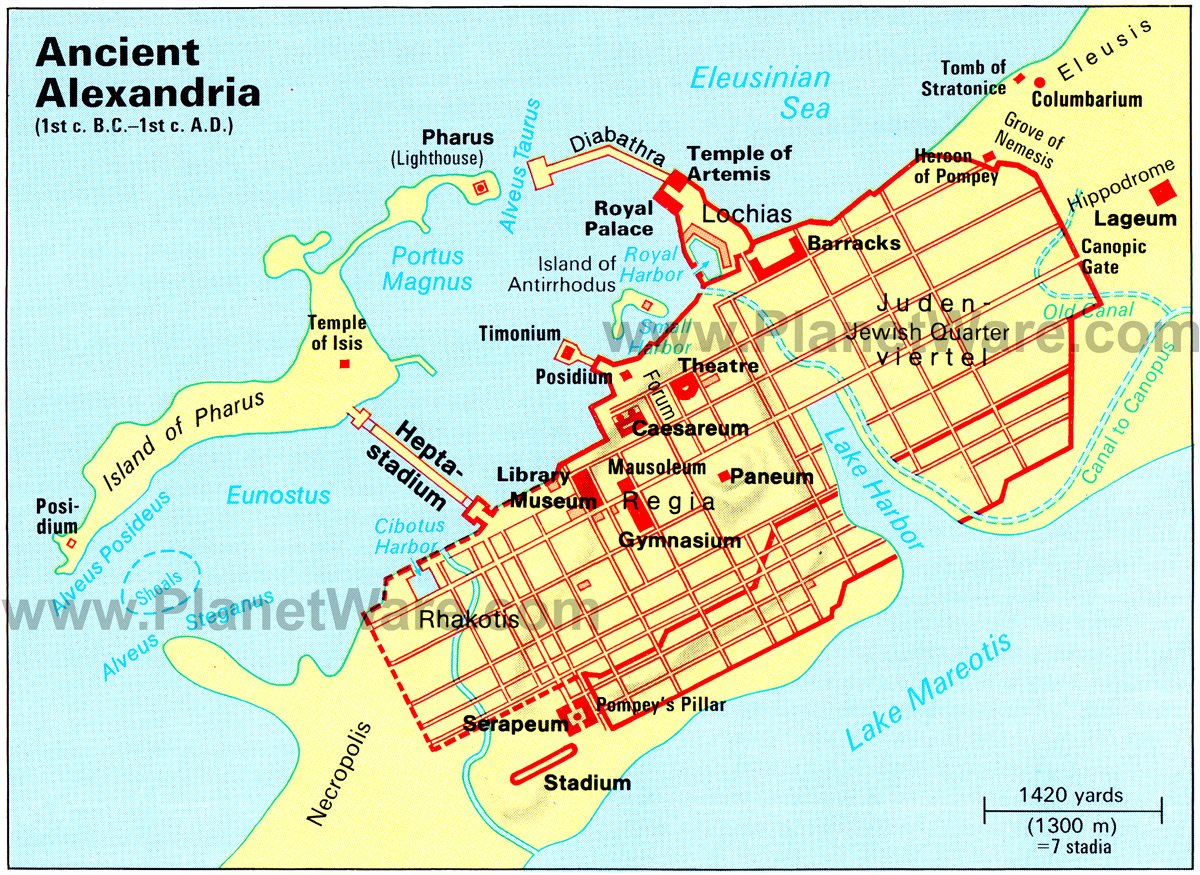

Great question! For those not familiar, I’ll start with a little background on the subject. The Library of Alexandria was founded by either Ptolemy I or his son, Ptolemy II, sometime in the third century B.C. Libraries were nothing new to ancient civilizations, though places to keep etched clay tablets might not be what we would consider a proper library today. The initial goal of the Library of Alexandria was most likely to flaunt Egypt’s enormous wealth rather than provide a place for study and research, but of course the library transformed into something much more.

Charged with collecting the knowledge of the world, many of the workers at the library were busy translating scrolls from “barbarian” languages into Greek. Scrolls were obtained from ancient “book fairs” in Athens and Rhodes. Scrolls from ships that made port were taken to the library and copied. Ptolemy III also borrowed the original manuscripts of Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides from Athens. According to Galen, the pharaoh had to pay a hefty price to guarantee that he would return the originals, but Ptolemy III had the scrolls copied and returned the copies. Because much about the library is wrapped in legend, we can’t be sure if this is true, or if it was a story told to show the power of Ptolemaic Egypt.

Needless to say, the library’s collection was vast, but the knowledge of exactly how many scrolls the library contained at any given point has been lost. Estimations range from 40,000 scrolls to 600,000. We do know that the collection spurred the need for a system of library organization. A precursor to today’s library catalogue was developed called Pinakes, or “tablets.” The tablets were divided into genre and sorted by the author’s name. It’s likely that this served as a record of the contents of the library rather than a precise system for finding the scrolls. Scrolls, unlike the books we know today, could not stand up on shelves but lay in heaps, meaning a precise method of organization would be nearly impossible to achieve. Unfortunately, the tablets along with the rest of the library have been lost to fire or time, meaning we have little record of the library’s exact contents.

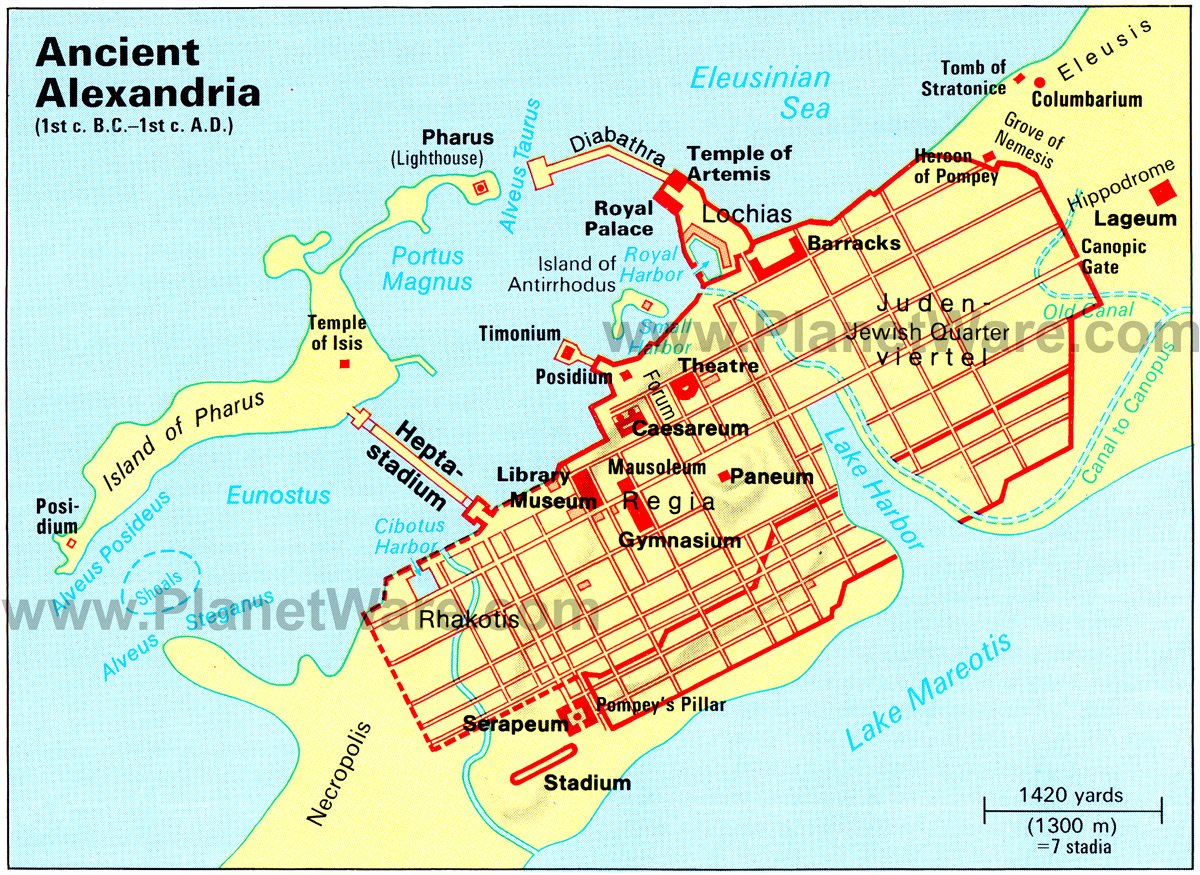

Partially because of the library, Alexandria became a seat of scholarship and learning. Scholars from all over the Hellenistic world were allowed to browse the library. They researched, discovered, and taught. It was at the library that Euclid wrote his groundbreaking work on geometry (much to the distaste of a majority of high school freshmen everywhere); Eratosthenes discovered how to measure the Earth’s circumference with remarkable accuracy; Herophilius learned that the brain controlled thought rather than the heart; and Aristarchus stated that the Earth revolves around the sun—1,800 years before Copernicus. The library represented a blending of cultures and minds and we have it to thank for many of our modern ideas about medicine, astronomy, math, and grammar.

Unfortunately, all good things must come to an end.

To answer your question specifically on what ever happened to the historic library, you’ll often hear it disappeared suddenly in a fire, but this probably isn’t accurate. What actually happened seems to have been a series of events over time that slowly led to the demise of the library.

More specifically, while there are several reports of fires in Alexandria linked to the destruction of the library, there is no solid historical evidence of the “great fire” believed to have destroyed the entire library. That being said, you’ll often hear three names bandied about as the top players in the library’s demise: Julius Caesar, Theophilius of Alexandria, and Caliph Omar of Damascus.

Legend has it that Theophilius, Patriarch of Alexandria in 391 A.D., began destroying pagan temples in the name of Christianity. The classical “pagan” scrolls contained in the library would have been a point of contention, as was the Serapeum temple attached to the library. If Theophilius destroyed a library in Alexandria, though, it is thought it was probably the “daughter library’ set up by Ptolemy III which contained far fewer scrolls than the historic great library. We do know that one of the rare historic mathematicians, philosophers, and astronomers who was female, Hypatia, was brutally murdered by a religious mob in Alexandria around this time (in 415 A.D.) demonstrating some of the strife between certain scholars and the religious in the region, though many scholars today think her death had more to do with her being caught up in political events than specifically her stance on Christianity.

The story about Caliph Omar is almost certainly made up. In 645 A.D., Omar conquered Egypt and supposedly burned the books in the library because they were not in line with the Koran’s teachings. Again, if Omar did burn a library it was probably the one rebuilt at the site of the original daughter library. Most historians think that this story was probably invented in the 12th century, and as with all stories that emerge long after they were said to take place, it should be considered with a grain of salt.

The most likely origin of the “great fire” theory is Julius Caesar’s actions during a war with Alexandria. Julius Caesar did set fire to the dockyards of Alexandria as well as the Alexandrine Fleet, which he documented in The Civil Wars. He doesn’t say whether or not the fire spread to the library, but it’s thought unlikely that it did, despite certain historic accounts. However, scrolls stored in warehouses along the harbour probably burned, and it is very likely that Caesar’s men looted the library and took a large number of scrolls back to Rome. Seneca wrote that 40,000 books were destroyed in Caesar’s fire, but if this is true, it would have probably been only a portion of the books that the library contained. Later writers, including Strabo and Seutonius, make mention of the museum of which the library was a part, as well as connections to the library scholars. This and other evidence demonstrates that the library survived, at least in part, past Caesar’s time—even if it, perhaps, never returned to the peak of its grandeur.

But if the library wasn’t destroyed by a fire and the original library isn’t standing today, then something must have happened to explain the loss of so much literature. If any one event contributed to the quick demise of the Library of Alexandria, it’s unknown to historians, contrary to popular belief. It is thought more likely that mundane things led to the “destruction” of the library, like time taking its toll on the amassed knowledge, with scrolls experiencing wear and tear and falling apart; the librarians at Alexandria faced tough decisions on which scrolls to continue to copy in the face of papyrus shortages. A few conquering emperors took many of the library’s works as spoils of war to other parts of the world, dispersing the texts. It’s possible religious leaders, taking offense to some of the contents, may have had some of the scrolls destroyed as well, though most historians think this latter factor to be wildly exaggerated. (Particularly around the 17th century on it became in vogue by secular scientists to rail against the ignorance and misguided notions of various religious groups, with Catholics tending to be public enemy number one. As a result, many myths popped up, such as that Medieval Christians thought the world was flat and the like- basically attempts to portray religious people throughout history as mindless mobs burning books and rejecting science at every turn, despite this being quite contrary to actual documented evidence on many of these popular stories.)

Whatever the case, the loss of the knowledge contained in the library is enough to still the heart of many an academic today, particularly with hints of such works as the lost “History of the World” three book set, the “Books of Berosus”, written around 290 B.C., and references to other such works that were once there, hinting at how much we’ve lost.

However, this story does have something of a happy ending. In 2002, another library was built near the site of the original Library of Alexandria. Bibliotecha Alexandrina aims to maintain the spirit of the original library. People from all walks of life are coming together with the aim to preserve knowledge, from rare ancient texts to a science museum to computer systems. Countries from all over the world have sent books in an attempt to rebuild the collection that was lost to history. This time, just in case, the building is virtually fireproof.

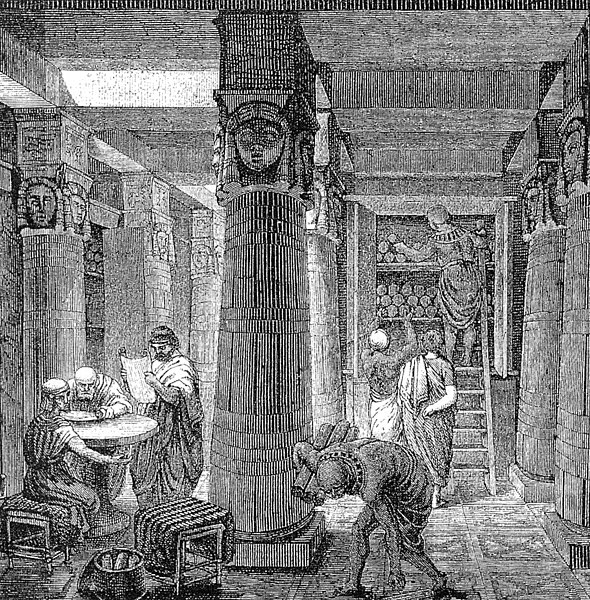

|

| Artist's rendition of the ancient Library of Alexandria |

Great question! For those not familiar, I’ll start with a little background on the subject. The Library of Alexandria was founded by either Ptolemy I or his son, Ptolemy II, sometime in the third century B.C. Libraries were nothing new to ancient civilizations, though places to keep etched clay tablets might not be what we would consider a proper library today. The initial goal of the Library of Alexandria was most likely to flaunt Egypt’s enormous wealth rather than provide a place for study and research, but of course the library transformed into something much more.

|

| Bust of Ptolemy I in the Louvre Museum |

|

| This granite statue depicts Ptolemy II in the traditional canon of ancient Egyptian art. Walters Art Museum, Baltimore. |

Charged with collecting the knowledge of the world, many of the workers at the library were busy translating scrolls from “barbarian” languages into Greek. Scrolls were obtained from ancient “book fairs” in Athens and Rhodes. Scrolls from ships that made port were taken to the library and copied. Ptolemy III also borrowed the original manuscripts of Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides from Athens. According to Galen, the pharaoh had to pay a hefty price to guarantee that he would return the originals, but Ptolemy III had the scrolls copied and returned the copies. Because much about the library is wrapped in legend, we can’t be sure if this is true, or if it was a story told to show the power of Ptolemaic Egypt.

|

| Gold coin depicting Ptolemy III issued by Ptolemy IV to honor his deified father |

Needless to say, the library’s collection was vast, but the knowledge of exactly how many scrolls the library contained at any given point has been lost. Estimations range from 40,000 scrolls to 600,000. We do know that the collection spurred the need for a system of library organization. A precursor to today’s library catalogue was developed called Pinakes, or “tablets.” The tablets were divided into genre and sorted by the author’s name. It’s likely that this served as a record of the contents of the library rather than a precise system for finding the scrolls. Scrolls, unlike the books we know today, could not stand up on shelves but lay in heaps, meaning a precise method of organization would be nearly impossible to achieve. Unfortunately, the tablets along with the rest of the library have been lost to fire or time, meaning we have little record of the library’s exact contents.

|

| This Latin inscription regarding Tiberius Claudius Balbilus of Rome (d. c. AD 79) mentions the "ALEXANDRINA BYBLIOTHECE" (line eight). |

Partially because of the library, Alexandria became a seat of scholarship and learning. Scholars from all over the Hellenistic world were allowed to browse the library. They researched, discovered, and taught. It was at the library that Euclid wrote his groundbreaking work on geometry (much to the distaste of a majority of high school freshmen everywhere); Eratosthenes discovered how to measure the Earth’s circumference with remarkable accuracy; Herophilius learned that the brain controlled thought rather than the heart; and Aristarchus stated that the Earth revolves around the sun—1,800 years before Copernicus. The library represented a blending of cultures and minds and we have it to thank for many of our modern ideas about medicine, astronomy, math, and grammar.

|

| 5th century scroll which illustrates the destruction of the Serapeum by Theophilus |

Unfortunately, all good things must come to an end.

To answer your question specifically on what ever happened to the historic library, you’ll often hear it disappeared suddenly in a fire, but this probably isn’t accurate. What actually happened seems to have been a series of events over time that slowly led to the demise of the library.

|

The Burning of the Library at Alexandria in 391 AD |

More specifically, while there are several reports of fires in Alexandria linked to the destruction of the library, there is no solid historical evidence of the “great fire” believed to have destroyed the entire library. That being said, you’ll often hear three names bandied about as the top players in the library’s demise: Julius Caesar, Theophilius of Alexandria, and Caliph Omar of Damascus.

Legend has it that Theophilius, Patriarch of Alexandria in 391 A.D., began destroying pagan temples in the name of Christianity. The classical “pagan” scrolls contained in the library would have been a point of contention, as was the Serapeum temple attached to the library. If Theophilius destroyed a library in Alexandria, though, it is thought it was probably the “daughter library’ set up by Ptolemy III which contained far fewer scrolls than the historic great library. We do know that one of the rare historic mathematicians, philosophers, and astronomers who was female, Hypatia, was brutally murdered by a religious mob in Alexandria around this time (in 415 A.D.) demonstrating some of the strife between certain scholars and the religious in the region, though many scholars today think her death had more to do with her being caught up in political events than specifically her stance on Christianity.

The story about Caliph Omar is almost certainly made up. In 645 A.D., Omar conquered Egypt and supposedly burned the books in the library because they were not in line with the Koran’s teachings. Again, if Omar did burn a library it was probably the one rebuilt at the site of the original daughter library. Most historians think that this story was probably invented in the 12th century, and as with all stories that emerge long after they were said to take place, it should be considered with a grain of salt.

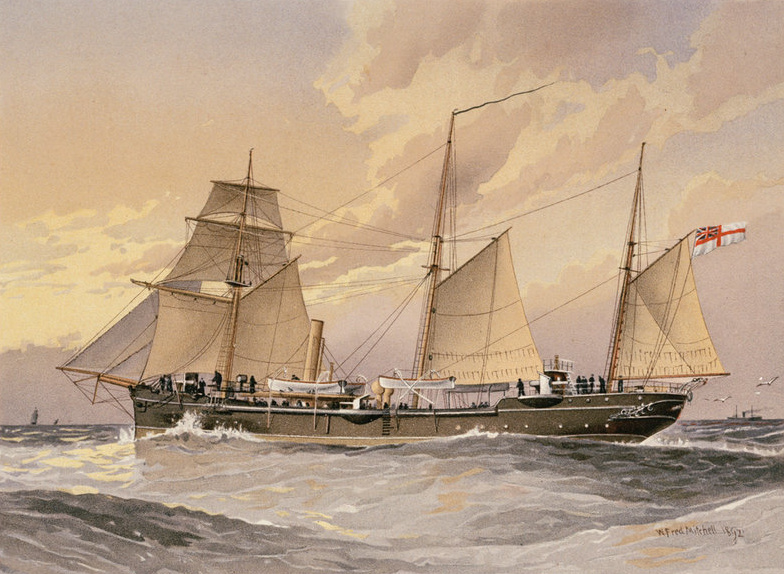

The most likely origin of the “great fire” theory is Julius Caesar’s actions during a war with Alexandria. Julius Caesar did set fire to the dockyards of Alexandria as well as the Alexandrine Fleet, which he documented in The Civil Wars. He doesn’t say whether or not the fire spread to the library, but it’s thought unlikely that it did, despite certain historic accounts. However, scrolls stored in warehouses along the harbour probably burned, and it is very likely that Caesar’s men looted the library and took a large number of scrolls back to Rome. Seneca wrote that 40,000 books were destroyed in Caesar’s fire, but if this is true, it would have probably been only a portion of the books that the library contained. Later writers, including Strabo and Seutonius, make mention of the museum of which the library was a part, as well as connections to the library scholars. This and other evidence demonstrates that the library survived, at least in part, past Caesar’s time—even if it, perhaps, never returned to the peak of its grandeur.

But if the library wasn’t destroyed by a fire and the original library isn’t standing today, then something must have happened to explain the loss of so much literature. If any one event contributed to the quick demise of the Library of Alexandria, it’s unknown to historians, contrary to popular belief. It is thought more likely that mundane things led to the “destruction” of the library, like time taking its toll on the amassed knowledge, with scrolls experiencing wear and tear and falling apart; the librarians at Alexandria faced tough decisions on which scrolls to continue to copy in the face of papyrus shortages. A few conquering emperors took many of the library’s works as spoils of war to other parts of the world, dispersing the texts. It’s possible religious leaders, taking offense to some of the contents, may have had some of the scrolls destroyed as well, though most historians think this latter factor to be wildly exaggerated. (Particularly around the 17th century on it became in vogue by secular scientists to rail against the ignorance and misguided notions of various religious groups, with Catholics tending to be public enemy number one. As a result, many myths popped up, such as that Medieval Christians thought the world was flat and the like- basically attempts to portray religious people throughout history as mindless mobs burning books and rejecting science at every turn, despite this being quite contrary to actual documented evidence on many of these popular stories.)

Whatever the case, the loss of the knowledge contained in the library is enough to still the heart of many an academic today, particularly with hints of such works as the lost “History of the World” three book set, the “Books of Berosus”, written around 290 B.C., and references to other such works that were once there, hinting at how much we’ve lost.

However, this story does have something of a happy ending. In 2002, another library was built near the site of the original Library of Alexandria. Bibliotecha Alexandrina aims to maintain the spirit of the original library. People from all walks of life are coming together with the aim to preserve knowledge, from rare ancient texts to a science museum to computer systems. Countries from all over the world have sent books in an attempt to rebuild the collection that was lost to history. This time, just in case, the building is virtually fireproof.

Bonus Fact:

- The library largely used papyrus for its scrolls and it’s thought that it never switched to parchment. It is thought by some historians that the library’s use of papyrus may in fact have indirectly caused the creation of parchment. Because so much papyrus was used for the library, exported papyrus was hard to come by, meaning an alternative writing material had to be developed.